Cimbri

The Cimbri (Greek: Κίμβροι, Kímbroi; Latin: Cimbri) were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic, Gaulish, Germanic, or even Cimmerian people. Several ancient sources indicate that they lived in Jutland, which in some classical texts was called the Cimbrian peninsula. There is no direct evidence for the language they spoke, though some scholars argue that it was a Germanic language, while others argue that it was Celtic.

Together with the Teutones and the Ambrones, they fought the Roman Republic between 113 and 101 BC during the Cimbrian War. The Cimbri were initially successful, particularly at the Battle of Arausio, in which a large Roman army was routed. They then raided large areas in Gaul and Hispania. In 101 BC, during an attempted invasion of the Italian peninsula, the Cimbri were decisively defeated at the Battle of Vercellae by Gaius Marius, and their king, Boiorix, was killed. Some of the surviving captives are reported to have been among the rebellious gladiators in the Third Servile War.

Name

[edit]The origin of the name Cimbri is unknown. One etymology[1] is PIE ‹The template PIE is being considered for deletion.› *tḱim-ro- "inhabitant", from ‹The template PIE is being considered for deletion.› tḱoi-m- "home" (> English home), itself a derivation from ‹The template PIE is being considered for deletion.› tḱei- "live" (> Greek κτίζω, Latin sinō); then, the Germanic *himbra- finds an exact cognate in Slavic sębrъ "farmer" (> Croatian, Serbian sebar, Belorussian сябёр syabyor).

The name has also been related to the word kimme meaning "rim", i.e., "the people of the coast".[2] Finally, since Antiquity, the name has been related to that of the Cimmerians.[3]

The name of the Danish region Himmerland (Old Danish Himbersysel) has been proposed to be a derivative of their name.[4] According to such proposals, the word Cimbri with a c would be an older form before Grimm's law (PIE k > Germanic h). Alternatively, Latin c- represents an attempt to render the unfamiliar Proto-Germanic h = [x] (Latin h was [h] but was becoming silent in common speech at the time), perhaps due to Celtic-speaking interpreters (a Celtic intermediary could also explain why one proposed etymology for the Teutons, Germanic *Þeuðanōz, became Latin Teutones).[citation needed]

Because of the similarity of the names, the Cimbri have been at times associated with Cymry, the Welsh name for themselves.[5] However, Cymry is derived from Brittonic *Kombrogi (cf. Allobroges), meaning "compatriots", and is linguistically unrelated to Cimbri.[6]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Scholars generally see the Cimbri as originating in Jutland, but archaeologists have found no clear indications of any mass migration from Jutland in the early Iron Age. The Gundestrup Cauldron, which was deposited in a bog in Himmerland in the 2nd or 1st century BC, shows that there was some sort of contact with southeastern Europe, but it is uncertain if this contact can be associated with the Cimbrian militia expeditions against Rome of the 1st Century BC. It is known that the peoples of Northern Europe and the British Isles participated in annual partial population seasonal Winter migrations southward to what is now central Iberia and southern France where goods and resources were traded and cross-culture marriages were arranged.[7]

Advocates for a northern homeland point to Greek and Roman sources that associate the Cimbri with the Jutland peninsula. According to the Res gestae (ch. 26) of Augustus, the Cimbri were still found in the area around the turn of the 1st century AD:

My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhine eastward as far as the lands of the Cimbri, to which, up to that time, no Roman had ever penetrated either by land or by sea, and the Cimbri and Charydes and Semnones and other peoples of the Germans of that same region through their envoys sought my friendship and that of the Roman people.

The contemporary Greek geographer Strabo testified that the Cimbri still existed as a Germanic tribe, presumably in the "Cimbric peninsula" (since they are said to live by the North Sea and to have paid tribute to Augustus):

As for the Cimbri, some things that are told about them are incorrect and others are extremely improbable. For instance, one could not accept such a reason for their having become a wandering and piratical folk as this that while they were dwelling on a Peninsula they were driven out of their habitations by a great flood-tide; for in fact they still hold the country which they held in earlier times; and they sent as a present to Augustus the most sacred kettle in their country, with a plea for his friendship and for an amnesty of their earlier offences, and when their petition was granted they set sail for home; and it is ridiculous to suppose that they departed from their homes because they were incensed on account of a phenomenon that is natural and eternal, occurring twice every day. And the assertion that an excessive flood-tide once occurred looks like a fabrication, for when the ocean is affected in this way it is subject to increases and diminutions, but these are regulated and periodical.

— Strabo, Geographica 7.2.1, trans. H. L. Jones[8]

On the map of Ptolemy, the "Kimbroi" are placed on the northernmost part of the peninsula of Jutland,[9] i.e., in the modern landscape of Himmerland south of Limfjorden (since Vendsyssel-Thy north of the fjord was at that time a group of islands).

Migration

[edit]Some time before 100 BC many of the Cimbri, as well as the Teutons and Ambrones, migrated south-east. After several unsuccessful battles with the Boii and other Celtic tribes, they appeared c. 113 BC in Noricum, where they invaded the lands of one of Rome's allies, the Taurisci.

On the request of the Roman consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, sent to defend the Taurisci, they retreated, only to find themselves deceived and attacked at the Battle of Noreia, where they defeated the Romans.[10] Only a storm, which separated the combatants, saved the Roman forces from complete annihilation.

Invading Gaul

[edit]Now the road to Italy was open, but they turned west towards Gaul. They came into frequent conflict with the Romans, who usually came out the losers. In 109 BC, they defeated a Roman army under the consul Marcus Junius Silanus, who was the commander of Gallia Narbonensis. In 107 BC they defeated another Roman army under the consul Gaius Cassius Longinus, who was killed at the Battle of Burdigala (modern day Bordeaux) against the Tigurini, who were allies of the Cimbri.

Attacking the Roman Republic

[edit]It was not until 105 BC that they planned an attack on the Roman Republic itself. At the Rhône, the Cimbri clashed with the Roman armies. Discord between the Roman commanders, the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio and the consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, hindered Roman coordination and so the Cimbri succeeded in first defeating the legate Marcus Aurelius Scaurus and later inflicted a devastating defeat on Caepio and Maximus at the Battle of Arausio. The Romans lost as many as 80,000 men, according to Livy; Mommsen (in his History of Rome) thought that excluded auxiliary cavalry and non-combatants who brought the total loss closer to 112,000. Other estimates are much smaller, but by any account a large Roman army was routed.

Rome was in panic, and the terror cimbricus became proverbial. Everyone expected to soon see the new Gauls outside of the gates of Rome. Desperate measures were taken: contrary to the Roman constitution, Gaius Marius, who had defeated Jugurtha, was elected consul and supreme commander for five years in a row (104–100 BC).

Defeat

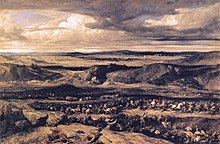

[edit]

In 104–103 BC, the Cimbri had turned to the Iberian Peninsula where they pillaged far and wide, until they were confronted by a coalition of Celtiberians.[11] Defeated, the Cimbri returned to Gaul, where they joined their allies, the Teutons. During this time, C. Marius had the time to prepare and, in 102 BC, he was ready to meet the Teutons and the Ambrones at the Rhône. These two tribes intended to pass into Italy through the western passes, while the Cimbri and the Tigurines were to take the northern route across the Rhine and later across the Central Eastern Alps.

At the estuary of the Isère, the Teutons and the Ambrones met Marius, whose well-defended camp they did not manage to overrun. Instead, they pursued their route, and Marius followed them. At Aquae Sextiae, the Romans won two battles and took the Teuton king Teutobod prisoner.

The Cimbri had penetrated through the Alps into northern Italy. The consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus had not dared to fortify the passes, but instead he had retreated behind the river Po, and so the land was open to the invaders. The Cimbri did not hurry, and the victors of Aquae Sextiae had the time to arrive with reinforcements. At the Battle of Vercellae, at the confluence of the river Sesia with the Po, in 101 BC, the long voyage of the Cimbri also came to an end.

It was a devastating defeat. Two chieftains, Lugius and Boiorix, died on the field, while the other chieftains Caesorix and Claodicus were captured.[12] The women killed both themselves and their children in order to avoid slavery. The Cimbri were annihilated, although some may have survived to return to the homeland where a population with this name was residing in northern Jutland in the 1st century AD, according to the sources quoted above. Some of the surviving captives are reported to have been among the rebelling gladiators in the Third Servile War.[13]

Justin's epitome of Trogus has Mithridates the Great send emissaries to the Cimbri to request military aid during the Social War (91-88 BCE).[14] Justin also states that the Cimbri were again in Italy at this time, i.e. over ten years later.[15]

Supposed descendants

[edit]According to Julius Caesar, the Belgian tribe of the Atuatuci "was descended from the Cimbri and Teutoni, who, upon their march into our province and Italy, set down such of their stock and stuff as they could not drive or carry with them on the near (i.e. west) side of the Rhine, and left six thousand men of their company there as guard and garrison" (Gall. 2.29, trans. Edwards). They founded the city of Atuatuca in the land of the Belgic Eburones, whom they dominated. Thus Ambiorix king of the Eburones paid tribute and gave his son and nephew as hostages to the Atuatuci (Gall. 6.27). In the first century AD, the Eburones were replaced or absorbed by the Germanic Tungri, and the city was known as Atuatuca Tungrorum, i.e. the modern city of Tongeren.

The population of modern-day Himmerland claims to be the heirs of the ancient Cimbri. The adventures of the Cimbri are described by the Danish Nobel Prize–winning author Johannes V. Jensen, himself born in Himmerland, in the novel Cimbrernes Tog (1922), included in the epic cycle Den lange Rejse (English The Long Journey, 1923). The so-called Cimbrian bull ("Cimbrertyren"), a sculpture by Anders Bundgaard, was erected on 14 April 1937 in a central town square in Aalborg, the capital of the region of North Jutland.

A German ethnic minority speaking the Cimbrian language, having settled in the mountains between Vicenza, Verona, and Trento in Italy (also known as Seven Communities), is also called the Cimbri. For hundreds of years this isolated population and its present 4,400 inhabitants have claimed to be the direct descendants of the Cimbri retreating to this area after the Roman victory over their tribe. However, it is more likely that Bavarians settled here in the Middle Ages. Most linguists remain committed to the hypothesis of a medieval (11th to 12th century AD) immigration to explain the presence of small German-speaking communities in the north of Italy.[16] Some genetic studies seem to prove a Celtic, not Germanic, descent for most inhabitants in the region[17] that is reinforced by Gaulish toponyms such as those ending with the suffix -ago < Celtic -*ako(n) (e.g. Asiago is clearly the same place name as the numerous variants – Azay, Aisy, Azé, Ezy – in France, all of which derive from *Asiacum < Gaulish *Asiāko(n)). On the other hand, the original place names in the region, from the specifically localized language known as 'Cimbro' are still in use alongside the more modern names today. These indicate a different origin (e.g., Asiago is known also by its original Cimbro name of Sleghe). The Cimbrian origin myth was popularized by humanists in the 14th century.[citation needed]

Despite these connections to southern Germany, belief in a Himmerland origin persisted well into modern times. On one occasion in 1709, for instance, Frederick IV of Denmark paid the region's inhabitants a visit and was greeted as their king. The population, which kept its independence during the time of the Venice Republic, was later severely devastated by World War I. As a result, many Cimbri have left this mountainous region of Italy, effectively forming a worldwide diaspora.[18]

Culture

[edit]Religion

[edit]

The Cimbri are depicted as ferocious warriors who did not fear death. The host was followed by women and children on carts. Aged women, priestesses, dressed in white sacrificed the prisoners of war and sprinkled their blood, the nature of which allowed them to see what was to come.

Strabo gives this vivid description of the Cimbric folklore:

Their wives, who would accompany them on their expeditions, were attended by priestesses who were seers; these were grey-haired, clad in white, with flaxen cloaks fastened on with clasps, girt with girdles of bronze, and bare-footed; now sword in hand these priestesses would meet with the prisoners of war throughout the camp, and having first crowned them with wreaths would lead them to a brazen vessel of about twenty amphorae; and they had a raised platform which the priestess would mount, and then, bending over the kettle, would cut the throat of each prisoner after he had been lifted up; and from the blood that poured forth into the vessel some of the priestesses would draw a prophecy, while still others would split open the body and from an inspection of the entrails would utter a prophecy of victory for their own people; and during the battles they would beat on the hides that were stretched over the wicker-bodies of the wagons and in this way produce an unearthly noise.

— Strabo, Geographica 7.2.3, trans. H. L. Jones

If the Cimbri did in fact come from Jutland, evidence that they practiced ritualistic sacrifice may be found in the Haraldskær Woman discovered in Jutland in the year 1835. Noosemarks and skin piercing were evident and she had been thrown into a bog rather than buried or cremated. Furthermore, the Gundestrup cauldron, found in Himmerland, may be a sacrificial vessel like the one described in Strabo's text. In style, the work looks like Thracian silver work, while many of the engravings are Celtic objects.[19]

Language

[edit]A major problem in determining whether the Cimbri were speaking a Celtic language or a Germanic language is that, at that time, the Greeks and Romans tended to refer to all groups to the north of their sphere of influence as Gauls, Celts, or Germani rather indiscriminately, and not based upon languages. Caesar seems to be one of the first authors to distinguish the Celtae and Germani, and he had a political motive for doing so, because it was an argument in favour of his push to set the Rhine as a new Roman border.[20] Yet, one cannot always trust Caesar and Tacitus when they ascribe individuals and tribes to one or the other category, although Caesar made clear distinctions between the two cultures. Some ancient sources categorize the Cimbri as a Germanic tribe,[21] but some ancient authors include the Cimbri among the Celts.[22]

There are few direct testimonies to the language of the Cimbri: referring to the Northern Ocean (the Baltic or the North Sea), Pliny the Elder states:[23] "Philemon says that it is called Morimarusa, i.e. the Dead Sea, by the Cimbri, until the promontory of Rubea, and after that Cronium." The contemporary Gaulish terms for "sea" and "dead" appear to have been mori and *maruo-; compare their well-attested modern Insular Celtic cognates muir and marbh (Irish), môr and marw (Welsh), and mor and marv (Breton).[24] The same word for "sea" is also known from Germanic, but with an a (*mari-), whereas a cognate of marbh is unknown in all dialects of Germanic.[25] Yet, given that Pliny had not heard the word directly from a Cimbric speaker, it cannot be ruled out that the word he heard had been translated into Gaulish.[26]

The known Cimbri chiefs have Celtic names, including Boiorix (which may mean "King of the Boii" or, more literally, "King of Strikers"), Gaesorix (which means "Spear King"), and Lugius (which may be named after the Celtic god Lugus).[27] Other evidence to the language of the Cimbri is circumstantial: thus, we are told that the Romans enlisted Gaulish Celts to act as spies in the Cimbri camp before the final showdown with the Roman army in 101 BC.[28]

Jean Markale[29] wrote that the Cimbri were associated with the Helvetii, and more especially with the indisputably Celtic Tigurini. These associations may link to a common ancestry, recalled from two hundred years previous, but that is not certain. Henri Hubert[30] states "All these names are Celtic, and they cannot be anything else". Some authors take a different perspective.[31]

Countering the argument of a Celtic origin is the literary evidence that the Cimbri originally came from northern Jutland,[31] an area with no Celtic placenames, instead only Germanic ones.[32][33] This does not rule out Cimbric Gallicization during the period when they lived in Gaul.[31] Boiorix, who may have had a Celtic if not a Celticized Germanic name, was king of the Cimbri after they moved away from their ancestral home of northern Jutland. Boiorix and his tribe lived around Celtic peoples during his era as J. B. Rives points out in his introduction to Tacitus' Germania; furthermore, the name "Boiorix" can be seen as having either Proto-Germanic or Celtic roots.[27]

In fiction

[edit]The science fiction story "Delenda Est" by Poul Anderson depicts an alternate history in which Hannibal won the Second Punic War and destroyed Rome, but Carthage proved unable to rule Italy – which fell into utter chaos. Thus, there was no one to stop the Cimbri two hundred years later. They filled the vacuum, conquered Italy, assimilated the local population to their own culture and by the equivalent of the 20th century had made of Italy a flourishing, technologically advanced kingdom speaking a Germanic language. He also wrote an unrelated historical novel "The Golden Slave", about a Cimbrian chieftain who is enslaved by the Romans after the Battle of Vercellae.

Cimbri is referenced in Italo Calvino's novel If on a Winter's Night a Traveller as a fictional country that warred with a similarly fictionalised version of Cimmeria, thus imposing its own written language onto the Cimmerians.

Jeff Hein's historical fiction series The Cimbrian War tells the story of the Cimbri and their migration across Iron-Age Europe.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Vasmer, Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, 1958, vol. 3, p. 62; Z. Gołąb, "About the connection between kinship terms and some ethnica in Slavic", International Journal of Slavic Linguistics and Poetics 25-26 (1982) 166-7.

- ^ Nordisk familjebok, Projekt Runeborg.

- ^ Posidonius in Strabo, Geography 7.2.2; Diodorus Siculus, Bibl. 5.32.4; Plutarch, Vit.Mar. 11.11.

- ^ Jan Katlev, Politikens etymologisk ordbog, Copenhagen 2000: 294; Kenneth W. Harl, Rome and the Barbarians, The Teaching Company, 2004.

- ^ C. Rawlinson, "On the Ethnography of the Cimbri", Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 6 (1877) 150-158.

- ^ C. T. Onions and R. W. Burchfield, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, 1966, s. v. Cymry; Webster's Third New International Dictionary. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 2002: 321.

- ^ Kaul, F.; Martens, J. (1995). "Southeast European Influences in the Early Iron Age of Southern Scandinavia. Gundestrup and the Cimbri". Acta Archaeologica. 66: 111–161.

- ^ As a geologist, Strabo reveals himself as a gradualist; in 1998, however, the archaeologist B. J. Coles identified as "Doggerland" the now-drowned habitable and huntable lands in the coastal plain that had formed in the North Sea when sea level dropped, and that was re-flooded following the withdrawal of the ice sheets.

- ^ Ptolemy, Geography 2.11.7: πάντων δ᾽ ἀρκτικώτεροι Κίμβροι "the Cimbri are more northern than all (of these tribes)"

- ^ Beck, Frederick George Meeson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 368.

- ^ Livy: Periochae 67

- ^ Sampson, Gareth S. (2010). The crisis of Rome: the Jugurthine and Northern Wars and the rise of Marius. Pen & Sword Military. p. 175. ISBN 9781844159727. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Strauss, Barry (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-4165-3205-7.

marius german.

- ^ Marcus Junianus Justinus, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, 38.3[usurped], 'In the next place, well understanding what a war he was provoking, he sent ambassadors to the Cimbri, the Gallograecians, the Sarmatians, and the Bastarnians, to request aid'

- ^ Marcus Junianus Justinus, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, 38.4[usurped], 'all Italy, at the present time, was in arms in the Marsian war,... At the same time, too, the Cimbri from Germany, many thousands of wild and savage people, had rushed upon Italy like a tempest', The Latin text has not like this translation an imperfect and a pluperfect, but two perfect infinitives (consurrexisse... inundasse...)

- ^ James R. Dow: Bruno Schweizer's commitment to the Langobardian thesis. In: Thomas Stolz (Hrsg): Kolloquium über Alte Sprachen und Sprachstufen. Beiträge zum Bremer Kolloquium über "Alte Sprachen und Sprachstufen". (= Diversitas Linguarum, Volume 8). Verlag Brockmeyer, Bochum 2004, ISBN 3-8196-0664-5, S. 43–54.

- ^ Pozzato, G; Zorat, F; Nascimben, F; Gregorutti, M; Comar, C; Baracetti, S; Vatta, S; Bevilacqua, E; Belgrano, A; Crovella, S; Amoroso, A (2001). "Haemochromatosis gene mutations in a clustered Italian population: evidence of high prevalence in people of Celtic ancestry". Eur J Hum Genet. 9 (6): 445–51. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200643. PMID 11436126.

- ^ Haselgrove and Wigg-Wolf, Colin and David (2005). Iron Age coinage and ritual practices. Von Zabern. p. 162. ISBN 9783805334914. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "The dating and origin of the silver cauldron". National Museum of Denmark. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ A.A. Lund, Die ersten Germanen: Ethnizität und Ethnogenese, Heidelberg 1998.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Gallic Wars 1.33.3-4; Strabo, Geographica 4.4.3, 7.1.3; Pliny, Natural History 4.100; Tacitus, Germania 37, History 4.73.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1.4.29, Illyrica 8.3.

- ^ Naturalis Historia, 4.95: Philemon Morimarusam a Cimbris vocari, hoc est mortuum mare, inde usque ad promunturium Rusbeas, ultra deinde Cronium.

- ^ Ahl, F. M. (1982). "Amber, Avallon, and Apollo's Singing Swan". American Journal of Philology. 103: 399.

- ^ Germanic has *murþ(r)a "murder" (with the verb *murþ(r)jan), but uses *daujan and *dauða- for "die" and "dead".

- ^ Accordingly, Pokorny, Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, 1959, p. 735, describes the word as "Gaulish?".

- ^ a b Rives, J.B. (Trans.) (1999). Germania: Germania. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-815050-4

- ^ Rawlinson, in Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 6 (1877) 156.

- ^ Markale, Celtic Civilization 1976:40.

- ^ Hubert, The Greatness and Decline of the Celts. 1934. Ch. IV, I.

- ^ a b c Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (2003). The Celts: A History. Boydell Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-85115-923-0.

- ^ Bell-Fialkoll, Andrew, ed. (2000). The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe: Sedentary Civilization v. "Barbarian" and Nomad. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 117. ISBN 0-312-21207-0.

- ^ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, Illinois, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5. This long-standing, well-known article on the languages can be found in almost any edition of Britannica.

External links

[edit]- Kennedy, James (1855). "On the Ancient Languages of France and Spain". Transactions of the Philological Society (11).

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. V (9th ed.). 1878. p. 780.

- . . 1914.